Brazil doing well.

Covid-19 impacts the economy, but agribusiness lives the best of its history. Time is for fat cows, but sustainability cannot be left out.

In the last few months, the 40-year-old gaucho Maurício De Bortoli has been dedicated to deciphering colors. They help you interpret soybean productivity on your 9,000-hectare farm in Cruz Alta, Rio Grande do Sul. It is not the trained eye of this third generation representative of a family of farmers that comes into action, but sensors that, coupled the probes installed in the soil, capture the light waves emitted by the plants and help Bortoli to make decisions in the field.

The electromagnetic signals are sent to software that decodes the colors of the plants and identifies the incidence of pests or the lack of nutrients. “With this, it is possible to know at a very early stage if the plant is sick and what needs to be done, using fertilizers or pesticides in the right measure,” says Bortoli.

The search for detail made the Bortoli farm become the champion in soybean productivity in the country in 2019 in the annual contest promoted by the Soja Brasil Strategic Committee, one of the most respected entities in the sector. His property produced 124 bags of grain per hectare (more than double the national average).

Currently, Bortoli produces about 1.1 million bags of soybeans per year on the farm created by his grandfather Aquelino. In 2018 and 2019, he reinvested about 15% of sales, over R $ 100 million, in new technologies. The management process was also improved, with the creation of a board of directors and the hiring of market professionals in leadership positions.

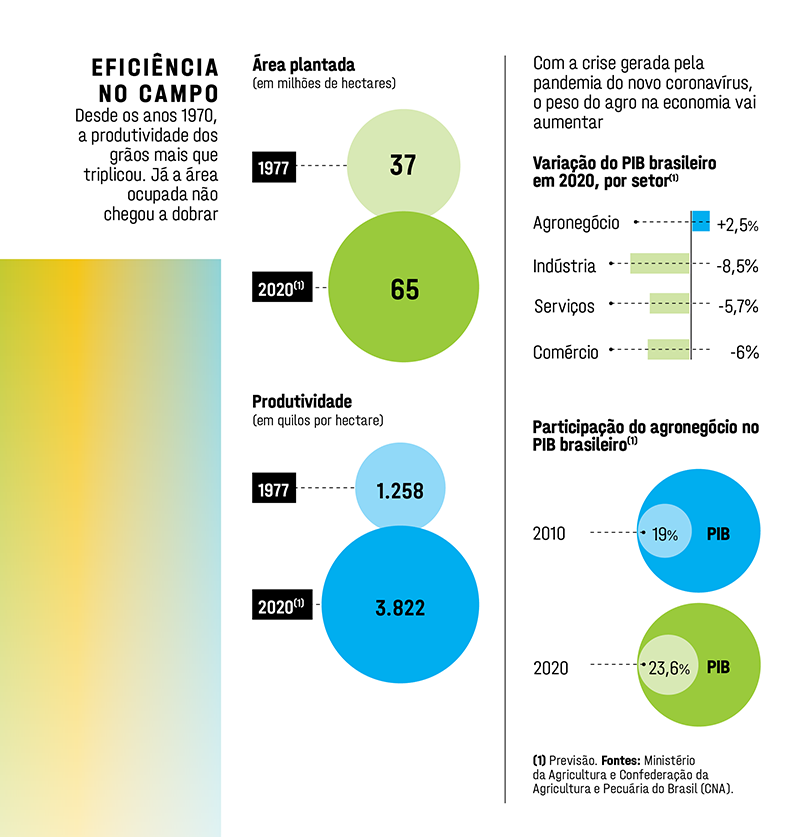

The achievements of rural entrepreneurs, such as those of the gaucho of Cruz Alta, encourage dark times for the Brazilian economy. The new coronavirus pandemic is expected to make the country’s gross domestic product shrink by up to 9%. But, while other sectors of the economy are expected to suffer bitter losses this year, agribusiness GDP is expected to grow 2.5%, reaching 728.6 billion reais.

“It will be the highest value obtained in history by the sector, something very positive in a year in which the economy is so staggering”, says economist Renato Conchon, economic coordinator of the National Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock (CNA). At the same time, the industry’s GDP is expected to shrink 7.9%, followed by a 9.8% drop in trade and 5.5% in services, according to a projection by FGV, which considers a total retraction of the Brazilian economy of 6 , 4%.

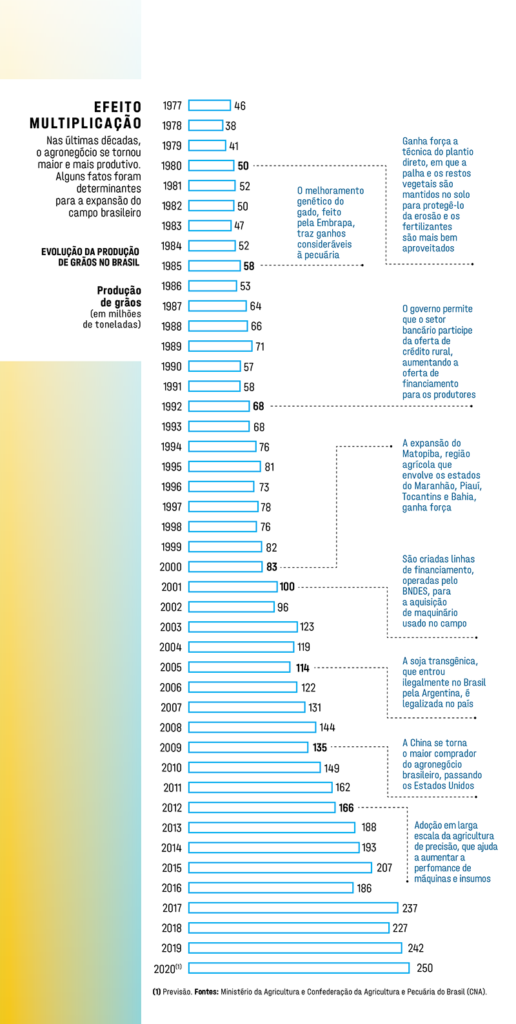

Agribusiness, which has been breaking record after record, should account for almost 24% of Brazilian GDP in 2020, a historic milestone. The 250 million ton grain crop is also expected to be the largest recorded so far. “Agribusiness is being instrumental in helping to mend the damage done to the economy by the coronavirus,” says economist Marcos Jank, professor and senior researcher of global agribusiness at Insper. And the future is promising: by 2027, Brazil should reach the mark of 300 million tons of grains.

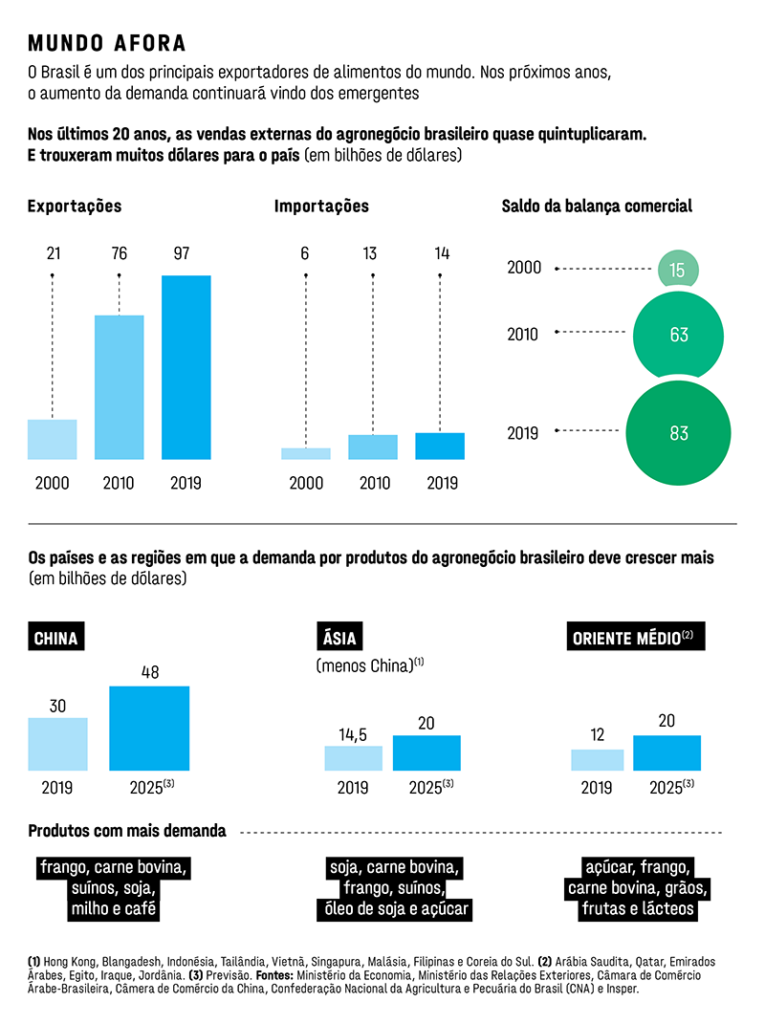

The ports of Paranaguá and Santos, where a large part of Brazilian production is transported, have never had so much movement. Food shipments increased 23% between January and April compared to the same period last year. According to calculations made exclusively for EXAME by economist José Garcia Gasques, general coordinator for Policy and Information Evaluation at the Agricultural Policy Secretariat of the Ministry of Agriculture, exports are expected to reach US $ 102 billion this year, an expansion of 6 %.

The record numbers of agribusiness in 2020 are possible because the sector is experiencing an increase in productivity that began in the 1970s. From that time on, a series of public policies and investments in the development of new technologies that were fundamental for the sector’s competitiveness gains. With the creation of the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa) in 1972, the development of seeds adapted to the tropical climate began – until then, they were imported from countries like the United States.

It was not long before new agricultural frontiers were opened, with the expansion to the Cerrado and to the region that became known as Matopiba, which involves part of the territories of Maranhão, Piauí, Tocantins and Bahia. The development of new planting systems, with the preservation of plant remains that cover the land and guarantee a greater presence of nutrients, was another important advance. “The generation of wealth and the productivity of agribusiness have not stopped growing for decades thanks to a public policy to encourage research, the technical guidance offered to producers and new technologies”, says Gasques.

With the agribusiness GDP growing, companies in the sector are hiring. This is the case of BRF, the world’s largest chicken exporter, which has already opened more than 2,000 vacancies in its various units across the country. The expectation is that the financial results will continue to grow. In the first quarter, the company recorded net revenue of almost 9 billion reais, 22% more than in the same period in 2019.

“The world demand for chicken, mainly from China and the Middle East, should continue to increase”, says Lourival Luz, president of BRF. Other companies in the sector are also surfing the good times. Marfrig Global Foods, the second largest beef industry in the world, should have the best year in its history. The expectation is that the company will reach a revenue of more than 60 billion reais this year, compared to 50 billion in 2019. The shares have accumulated a 35% increase so far. “Exports are increasing due to a series of global factors and also because the country is seen as a reliable partner, which has not had its production chain affected by the coronavirus,” says Miguel Gularte, president of Marfrig.

In the United States, more than 30 beef, pork and chicken factories had to suspend their activities in April and May because of the death of employees due to the coronavirus – among them are the units of the Brazilian JBS. In Brazil, there were also cases of covid-19 in refrigerators. Despite the still limited impact, on June 30, the Chinese government disabled four slaughterhouses in the country, including plants by JBS and Marfrig, in Rio Grande do Sul and Mato Grosso.

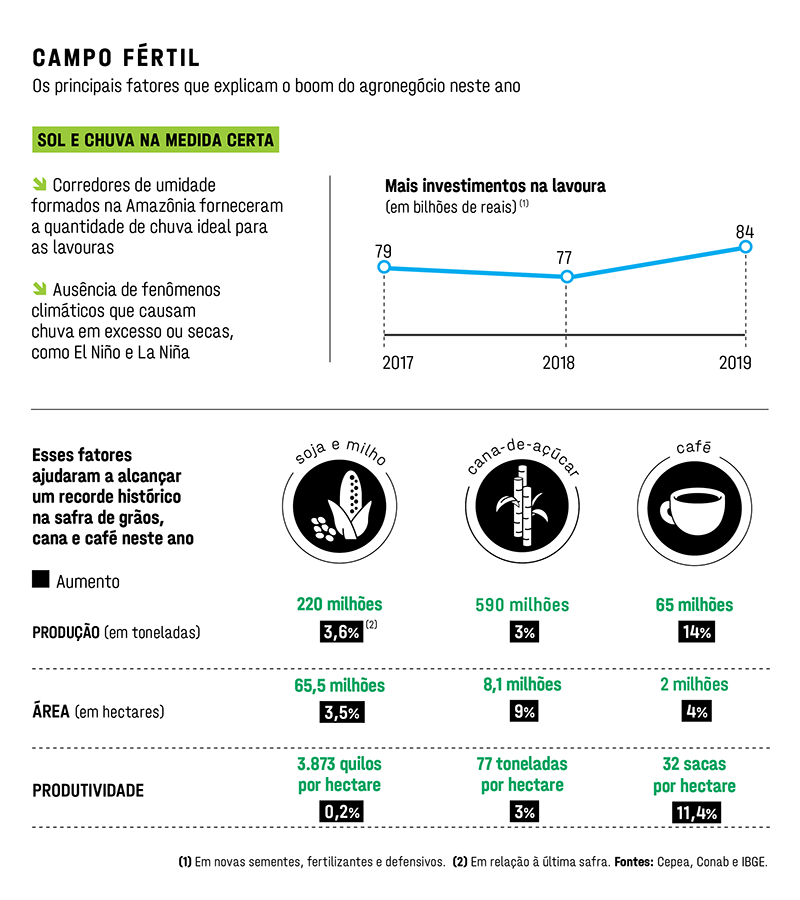

It is not only the international demand that has helped agribusiness in 2020. Climatic conditions and the conjuncture also play in favor. In May of last year, the American Center for Meteorology and Oceanography, in the United States, already pointed out that this year there would be neither El Niño nor La Niña, climatic phenomena that cause excessive rain or drought.

In addition, moisture corridors in the Amazon were formed in order to cause rain at the right time and in the exact amount, mainly in the Midwest and Southeast. The Northeast Region also benefited from rains, due to the cooling of the Atlantic in the Northern Hemisphere and the warming in the Southern Hemisphere. There is no news of all these phenomena happening simultaneously, which favors Brazilian agriculture in a unique way.

The planning of agribusiness entrepreneurs also counted points. “Producers increased investments in 2019 with an eye on the almost certain opportunities of 2020”, says Conchon, from CNA. The investments in new inputs, such as more productive seeds and last generation fertilizers, totaled 84 billion reais in planting the harvest harvested in 2020, 10% more compared to the previous cycle. This is a reflection of a new generation coming to agribusiness.

A survey by the McKinsey consultancy, carried out with 750 farmers from all over the country, reveals that more than 70% of young people up to 35 years old are more willing to acquire sensors and machines that work with advanced technologies, such as the internet of things. In the 35-45 age group, the percentages are similar. “The grandchildren of the founders of the farms are making a revolution in the countryside,” says Nelson Ferreira, a senior partner at McKinsey. “They keep up with trends and learn from older generations that the secret is to bring together productivity, new technologies and well-planned planning.”

Luciana Dalmagro, 34, belongs to the fourth generation of a family of rural producers. She has been managing her father’s farm, Paulo Portugal for five years, and has made the property located in Sales Oliveira, in the interior of São Paulo, one of the largest and best equipped farms in the country, with 3 million birds slaughtered per year. There, it invested in traceability and animal welfare systems that allow the export of all production to customers in Europe looking for high-end products.

Equipment that simulates sunrise and sunset makes chickens “happier”. In addition, there is more space for them: 13 birds are raised per square meter, 10% less than the usual average. According to market estimates, the turnover of farms with these characteristics is a few million reais per year. Dalmagro has a degree in pharmacy, a master’s degree in science and an MBA in business – she is the first in the family to study MBA. “I want to become a top 10 manager, something increasingly important in agriculture,” he says.

The commercial and political war between the United States and China has also helped Brazil. In June, in the last bidding for disputes between the two countries, the Chinese government instructed the main state-owned agricultural companies to stop buying products from the United States. The Chinese did not like American President Donald Trump’s criticisms of a new law that could jeopardize the autonomy of Hong Kong, territory that belongs to China. Since 2018, the trade dispute between the two largest powers in the world has increased import tariffs side by side, making agricultural products more expensive. “Brazil, with its immense production, is the main beneficiary of this dispute”, says Gasques.

For the first time in history, Brazilian corn shipments to China exceeded American exports to the country. Between January and April, Brazil sold 37 million tons of corn to China, while the Americans exported 35 million tons. The devaluation of the real against the dollar and the high grain productivity in Brazil created even more attractions for the Chinese market.

Brazilian grains were 23% cheaper than American ones. Much of the success of agribusiness is a result of China’s growing demand for food. Brazil’s largest trading partner, the country bought $ 30 billion in agricultural products last year. The expectation is that by 2025 this figure will reach 48 billion dollars – an increase of 60%.

The rural producer Enio Fernandes monitors the agribusiness variables on the international market daily. Owner of three farms in Palestine, in Goiás, which add up to 5,000 hectares with soy, corn and sugar, he realized that there was a new opportunity on the horizon. In 2018 and 2019, a fatal virus that affects only pigs decimated half of the Chinese herd, causing the death of 175 million animals. The market, as a whole, realized that Chinese demand for animal protein – not only from pigs but also from poultry and cattle – would enter an increasing spiral.

Therefore, Fernandes decided to invest, for the first time, in livestock. In 2019, he bought 2,000 head of cattle. This year, the sale of cattle for export is expected to increase farm revenues by 20%, reaching R $ 25 million. “Just like in the most competitive companies in the country, I do a well-structured investment plan”, he says.

Despite all this, Brazil still has important challenges to overcome. One is the lack of connectivity in the field. Less than 40% of the rural area has a 4G signal. Inside the farms, the situation is even worse. “The signal fails a lot, and most producers have difficulty using modern, autonomous sensors and machines”, says Claudio Frischtak, from Inter.B, a consultancy that carried out a study on the topic. “The solution is to reduce the bureaucracy of the antenna installation process and regulatory changes in the sector.”

The authorization for the installation of towers and antennas, which depends on the approval of each city hall, usually takes months on end. Plenty of paperwork is required for the walking process. Many operators give up expanding internet coverage in the interior due to bureaucracy. To solve this, only even with the hammer. Last year, a bill was created, known as the General Antenna Law, which stipulates that if there is no response on licensing requests within 60 days, the infrastructure supporting the telecommunications networks will be installed anyway, with or without a license. The law is still pending in the Senate.

Meanwhile, stories of losses due to the precariousness of connectivity are repeated. Farmer Fabio Tardivo, 31, who cultivates 1,400 hectares of soy and cane on two properties, one in Batatais, in the interior of São Paulo, and the other in Capetinga, in Minas Gerais, has already lost count of how many times he has machines stopped in the field due to lack of internet signal.

“The signal is so weak that many times not even WhatsApp works, and employees in the field are unable to communicate with me when a problem occurs,” he says. “We waste time and productivity.” The minister of agriculture agrees that it is essential to take the internet signal to the countryside. “Without connectivity, the producer cannot use the new technologies that collaborate to increase productivity,” Tereza Cristina told EXAME (read interview below).

The drama of the lack of antennas is a problem with a simple solution compared to the environmental risk that hangs over Brazilian agribusiness. Deforestation in the Amazon peaked in the last 11 years in 2019, and in the first five months of this year alone, forest clearing increased 34%. In May, 829 square kilometers in the Amazon were destroyed, 12% more than in the same period last year, according to the Real Time Deforestation Detection System (Deter), from the National Institute for Space Research (Inpe). In August last year, the increase captured by Deter transformed Brazil into an environmental villain on a global scale.

After almost a year, the country has not learned its lesson. Minister Ricardo Salles, of the Environment, made harmful comments to environmental preservation at the ministerial meeting on April 22, which was recorded and soon traveled the world. Salles said it was time to “go over the cattle” and change the rules for protecting the environment, since the media would be focused on coronavirus coverage. The international damage of the minister’s speech took on gigantic proportions.

“After that, the problem reached a new level, with international investors threatening to reduce investments in Brazil,” says Marcello Brito, president of the Brazilian Agribusiness Association. In June, a group of international investors that manages 3.75 trillion dollars in assets sent a letter to the Brazilian embassy in eight countries showing concern about the lack of public policies for forest conservation. The Norwegian fund Storebrand Asset Management, which manages $ 80 billion in assets worldwide, is one of the signatories to the letter.

“We intend to maintain our investments in Brazilian companies, but there is a need for more predictable regulation in relation to environmental policies that are aligned with sustainability”, Jan Erik Saugestad, president of the fund, told EXAME. Today, Storebrand has 117 million dollars invested in 57 Brazilian companies. In May, 40 European companies, among them the British Tesco, one of the largest in the supermarket sector in the world, threatened to boycott Brazilian products if the government does not take concrete actions to reduce deforestation.

Without advancing in sustainability, it is unlikely that agribusiness will make new leaps in growth, especially in relation to exports. “Today, having a negative image on the international stage in matters related to the environment can bring concrete retaliation in the field of international trade and investments,” says ambassador Rubens Ricupero.

In Brazil of successful agribusiness, the story is quite different. There are plenty of good examples of producers linked to innovation and sustainability. At the beginning of this report, Maurício De Bortoli, the champion in Brazilian soybean productivity, is proud to invest in technologies that not only increase productivity but also help to protect the environment, with less use of pesticides and other chemicals. Luciana Dalmagro, who exports all chicken production to Europe, placed hundreds of solar panels on her farm and invested in reusing water to make the business more sustainable. The Brazil of the new generations of rural producers is a hit. There is a lack of infrastructure and public policies to help.

IS AGRO POP? NOT IN THE BRAZILIAN STOCK EXCHANGE

For governance and volatility, companies avoid going public | Denyse Godoy

Despite its importance to the Brazilian GDP, agribusiness has a timid presence on the stock exchange. Those who want to participate in the success of national agriculture and livestock find few options to become a partner by buying a slice of companies in the sector at B3. The most important segment is meat. JBS, owned by brothers Joesley and Wesley Batista, weighs 2% on Ibovespa, B3’s main stock index.

BRF, owner of Sadia and Perdigão, and Minerva are also in the index, but it is Marfrig, which manufactures hamburgers for chains like McDonald’s, the best performing food processor. Its market value has multiplied by almost 3 since 2016, while the Ibovespa rose 62% and is close to the record, at 8.7 billion reais. Pulp production is represented by Suzano and Klabin, while the sugar and alcohol sector has Cosan. Even so, the share of these groups, 6.6%, is equivalent to one third of that of banks. Other segments do not even appear among the big ones.

Grain and fiber, with Terra Santa and SLC Agrícola, fertilizer, with Heringer, and beneficiation, with Camil, rice and beans, are not even part of the Ibovespa. The fruit one has only Pomifrutas, which went bankrupt in February. The first reason that keeps agribusiness off the stock exchange is corporate governance. Often, these are family companies, with unprofessional management, indefinite succession and lack of interest in satisfying minority investors.

The second is the volatility of agricultural commodities. Uncontrollable natural phenomena, such as rain, cause fluctuations in the price of goods that greatly affect stock prices. “A sudden fall could put a company at risk because of a seasonal factor,” says agronomist Patrícia Amélia Bueno, founder of the promotion and innovation consultancy EasyHub and a member of the agribusiness working group of the Brazilian Institute of Corporate Governance.

For these particularities, the stock exchange is not, in the opinion of many experts, the best alternative for an agricultural company to raise funds. The debt market, by contrast, has been more friendly. The possibility of offering guarantees such as land or machinery makes it easier to obtain money, and the creation of new tools in recent years has attracted the small investor.

The stock of Agribusiness Receivables Certificates (CRAs), which are the most famous security, grew 44% since the end of 2017, reaching R $ 43.2 billion in June. “The growth of investment retail has driven CRAs. They are an excellent alternative for smaller companies to access the credit market ”, says Odilon Costa, fixed income specialist at EXAME Research, EXAME’s investment analysis unit.

MORE INTERNET AND LESS DEFORESTATION

The new leap in agribusiness productivity depends on advancing internet coverage and sustainability policies | Carla Aranha

Last year was busy for Minister Tereza Cristina, from Agriculture. There were more than 17 trips to countries like China, Indonesia and Egypt. The objective was to open doors for Brazilian agribusiness – and, often, also to put warm cloths in the controversies in which the Brazilian government was involved. Now, in the face of the coronavirus pandemic, priorities have gained new focus. In an exclusive interview with EXAME, the minister comments on the main opportunities and weaknesses of Brazilian agribusiness in a new international scenario.

How do you see the increase in deforestation in the Amazon and the economic consequences of this for Brazil?

Indeed, deforestation has increased. This is already stated and is undeniable. There is much to be done to reverse this situation. I am a defender of the environment. In June, the plan to combat deforestation, conducted by the Vice-Presidency, was completed with goals to reduce deforestation and increase land tenure regularization. Now we have to face the fires in the Amazon again, which start again in August.

How to solve both problems?

A government operation was created to curb illegal activities, such as land grabbing, mining ores and logging in the Amazon, in which I worked. In relation to fires, this month we will start work on technical assistance to small producers in the Amazon, which in general do not have guidance on good agricultural practices.

Why this year will the Safra Plan allocate 30% more subsidies for rural insurance?

We are allocating 236 billion reais, 6% more than last year, to meet the greatest difficulties for producers. One is access to insurance, which is expensive in Brazil. With this subsidy, the producer will be able to separate a larger part of the revenue for the acquisition of new technologies, including those that collaborate for sustainability.

What does the country need to do for agribusiness to advance further?

We need to improve 4G coverage in the field. We have fantastic technologies, but it is often not possible to access them because the internet goes down all the time. We need to resolve this issue. Our transportation infrastructure, which has already advanced, is still something that makes Brazil cost more, so it also needs to be improved.

How did the pandemic impact agribusiness?

Brazil imports a large part of some inputs used in fertilizers. One is potassium. With the coronavirus, it became clear that we cannot depend so much on imports of such essential products. We are developing alternatives to expand their local manufacturing.

And what are the untapped opportunities?

There are many. We can, for example, increase fruit shipments. When I was in India, I saw that there is room to export more coffee and even sesame, which is widely consumed there. Brazil may become the world’s largest agribusiness power.

Source: www.exame.com/